Features

Pride in Place: Why Seattle Architecture Shines

Seattle's Past Influences its Modern-Day and Future Architecture

By Rachel Gallaher April 24, 2023

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2023 issue of Seattle magazine.

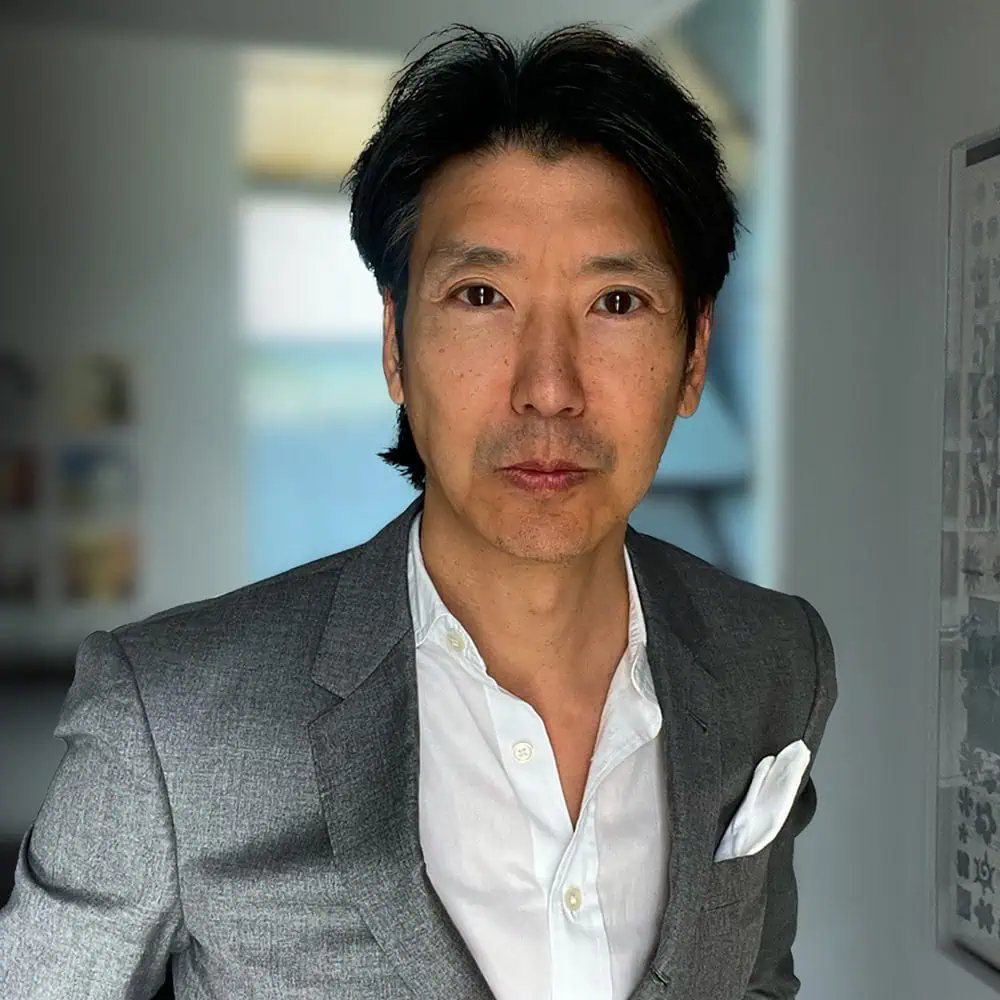

George Suyama has had an outsized influence on much of what we know as modern-day Seattle, but he never planned on a career in architecture.

Suyama, a Seattle native who has been practicing architecture in the region for more than six decades, founded his award-winning firm, George Suyama Architects (now Suyama Peterson Deguchi), in 1971. He has designed custom residences, resorts, galleries, theaters, restaurants, offices and retail spaces, and has become one of a handful of architects whose vision shaped Seattle’s unique, freewheeling architectural style.

“More than anything else, we have a sense of place,” says Suyama, who has received countless honors, including being elected to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) College of Fellows; being given the prestigious AIA Medal of Honor, the group’s highest award; and being inducted into the Residential Architect Magazine Hall of Fame. “When we try to emulate something stylish or trendy that you might see on the East Coast, it tends to fall flat or feel misplaced here.”

Without hundreds of years of precedence, Seattle grew at the hands of Suyama and other eager architects who didn’t set out to establish a new style, but — deeply influenced by place and setting — captured the zeitgeist of the region through their designs. While these visionaries might not be household names, you see their influence every time you walk through Seattle Center, visit Colman Park, or stroll along Alki Beach Park.

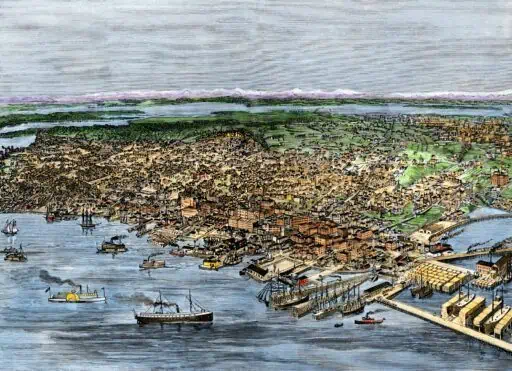

Everything in Seattle was built in the last 150 years. White settlers didn’t come to the city until 1851. The 1889 Seattle Fire devastated the downtown commercial district and created a blank slate onto which the city would rebuild at a larger metropolitan scale. Buildings constructed with brick, stone, and heavy timber rose up to six stories, replacing the rudimentary two- and three-level structures that had previously made up the city.

As a result, Seattle has always been an outlier, untethered from the traditions, institutions, and cultural norms that shaped the rest of the country. Today, there isn’t a singular look that visually ties everything together.

Cities such as Paris, New York, and Kyoto have hundreds, if not thousands, of years of history —and just as many years of cultural and artistic development. Seattle does not. Many impressive and culturally significant architectural and civic works, such as the wide boulevards of Paris, were built in celebration or at the behest of emperors and kings.

“You don’t need something to jump out at you because it’s more about the views than the buildings,” says Jim Olson, a founding principal at design firm Olson Kundig, who has been practicing in the Northwest for more than 60 years. “European cities have created these great, historic landmarks. We have the Space Needle, but we also have the Olympic Mountains, the lakes, Mount Rainier. Those are our Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe.”

The spirit of exploration that brought people to the Pacific Northwest is rooted in the fabric of the city and has guided the emergence of any sort of architectural “style.” Architects have been making up their own rules since they arrived, reaching into their individual creative wells to construct a tapestry of designs aligned more by guiding principles than outward appearance. The results are loosely cohesive, but not monolithic.

B2A4M1 Birds-eye view of Seattle, Washington circa 1890. Hand-colored woodcut

Image courtesy of North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy

“Seattle architects today appear most united by certain shared values,” writes architect and UW Department of Architecture Professor Jeffrey Karl Ochsner in the second edition of his book Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects. “There is also recognition of the importance of the natural environment and concern that it be respected and conserved, both at the level of individual project design and in relation to regional resources.”

It’s difficult to come up with a sharp, overarching definition — and that in itself is a very “Seattle” approach. Even though there was a period of time in the mid-20th century when a cohesive regional style emerged, designers and architects in the area have always done things their own way.

One stylistic influence is the Pacific Rim — specifically Japan. With a dedication to utility and non-gratuitous design, many tenets of Japanese architecture fit well in a region that prizes its natural beauty and doesn’t have a long legacy of superfluous, overwrought buildings.

“When you look at the approach to landscape (in the Pacific Northwest), you can say that it’s similar in Japan,” Olson says. “The most beautiful element is the landscape itself, and the architecture is supportive of your experience of that landscape. I think that’s worked its way into what we do here because we have such a remarkable setting.”

Suyama notes that the Japanese aesthetic has been a hugely influential factor in his work. “My whole life is a sequence of unplanned events that just sort of fit together in a way so that now I don’t know what I would have done if I had not become an architect,” he says. “When I first started my career, (architect) Gene Zima had an antique gallery that imported mingei — simple, pedestrian Japanese (folk art) artifacts. That was my first opening into an aesthetic that I glommed onto.”

One of Suyama’s lauded projects is the Junsei House, a minimal structure built on the lot next door to his and his wife’s primary residence. Five years after they moved into a home that Suyama built on West Seattle’s waterfront, the plot adjacent to theirs went up for sale, and, worried about what might go in, the couple purchased it.

In 2015, Suyama finished construction on a 2,000-square-foot building on that lot. The Junsei House — junsei means “pure” in Japanese — is 18 feet wide by 80 feet long, the largest he could go without disturbing the existing trees; he also built the structure on raised columns to avoid disturbing tree roots. Paring details to their simplest iteration, Suyama used modest, brown-stained plywood for the walls and ceiling.

A white box structure in the center of the house holds the main bedroom, bathroom, stairwell, kitchen, and loft, and a 19-foot high wall of windows at the back reveals an old cedar tree that gives glimpses of Puget Sound through its branches. The house is a study of purity and minimalism — the concept of withholding to create more feeling or meaning.

“Jim (Olson) and I started with the same sensibility,” Suyama says. “Looking at the latter part of our professional careers, we’ve diverged to the point where he has these intricately beautiful, composed (structures), and I’m eliminating everything to get down to a bare-bones situation. That’s fascinating to me.”

y the early 1910s, a new wave of academically trained architects was arriving from the East and the Midwest. Many of them had spent time in England and Germany. In his book, Ochsner writes, “This may account for the relatively strong local influence during this period of various English and northern European modes, and the Arts and Crafts movement.”

One of the most prominent architects to emerge in Seattle at this time was Chicago-born Ellsworth Storey, whose influential work (and fondness for the typology of Swiss chalets) is still seen today in residences around the city, including a set of 12 cottages next to Colman Park.

Constructed between 1912 and 1915 using local materials, the cottages — which have wood frames, large porches, and shingled roofs — are a response to their surrounding forested environment, and a forerunner to the Pacific Northwest Modernism movement that would sweep the region in the decades to come.

By the end of World War II and in the following decades, Modernism —an architectural style based on function, minimalism, and the rejection of ornamentation, among other characteristics — ascended as the dominant form of residential design in the Northwest. Globally, the movement emphasized asymmetry, open floor plans, large windows, and the use of materials such as concrete and steel in innovative ways.

Seattle architects reinterpreted this style through their unique regional lens, working with flat roofs and unpainted wood and doubling down on the indoor/outdoor connection through views and the streamlining of exterior living space with patios, decks, and yards.

Top practitioners of the era, who greatly influenced the trajectory of architecture in Seattle, include Paul Thiry, Paul Hayden Kirk, Roland Terry, Lionel Pries, Fred Bassetti, and John Graham Jr., who designed the Space Needle along with Victor Steinbrueck and Edward Carlson. All either attended or taught at the University of Washington.

Although the men are better known, a handful of women architects helped shape the Northwest Modernist movement. Mary Lund Davis attended UW in the early 1940s and, although she wasn’t the first woman architect to graduate from the school, she was the first after World War II.

She entered the design field at an exciting and stylistically progressive time. Her residential projects used natural wood and finishes, experimented with shapes and modularity, and worked to cut costs while not diminishing style.

“When it comes to architecture, there is a danger of being pulled in by the visual,” says Susan Jones, founder of Seattle-based architecture firm atelierjones. A Northwest native, Jones has been at the forefront of the sustainability in architecture movement for more than three decades, and she is one of the country’s leading experts in working with mass timber, a sustainably grown, engineered wood product. “While that is a huge part of it, we need to think more broadly about the role of architecture in our city and what it means to look beyond [the idea] of ‘style’ to how things are made.”

Another substantial influence emanates from the presence and history of Native American buildings, which included the communal longhouses in the region. “If you go back to pre-contact days, there was an emphasis on working and living in a collective environment integrated with its natural surroundings,” says Jones, who uses that history and approach as a touchstone for her work.

When the Space Needle made its debut at the 1962 Century 21 Exposition, it was joined by a coterie of structures that, according to Ochsner, showcased advancements in building technology.

Minoru Yamasaki’s United States Science Pavilion (now known as the Pacific Science Center) was a set of windowless concrete boxes made from 475 precast concrete panels transported 25 miles to their current site. At the time of its construction, the building was believed to be the largest single-use of precast concrete structural components in the country.

The Washington State Coliseum (now Climate Pledge Arena) is still known for its unique structure. Originally built with its paraboloid roof suspended from concrete beams, the arena underwent the first of a set of renovations in the mid-1990s, at which time the suspension portion of the roof was replaced with a series of trusses.

In 2018, Olson Kundig completed a renovation of the Space Needle. With 196% more glass than before — all the better to take in the 360-degree views of the city — and the world’s first and only revolving glass floor, the project modernized the landmark but retained the spirit and innovative thinking that led the original design.

“The fascinating thing about Seattle architecture is the way it makes use of structural engineering,” Ochsner says. “When we look at the downtown core, some buildings reflect extraordinary advances in the field.”

He names the First National Bank Building, the Norton Building, and the Kingdome as examples. “From a sports point of view (the Kingdome) became obsolete, but from an engineering point of view, it could have stood for 1,000 years.”

This experimental approach, and willingness to take risks, is another cultural touchstone that weaves its way through the history of Seattle. A city of free thinkers has made advancements in the fields of technology, medicine, transportation, and commerce, so it’s no surprise that the region would also foster progressive developments in building, construction, and the development of materials.

“Seattle is a sleeper city in the sense that people don’t generally think of it as being architecturally prominent,” says Kailin Gregga, a partner at Best Practice Architecture, “and yet we have more and more architects moving here to practice.”

Part of this attraction has to do with the innovative work happening locally. In the face of rapid population growth and climate change, sustainability is at the forefront of many design projects in the city. When it comes to building materials, Jones, a third-generation Northwesterner, praises regionally-sourced, cross-laminated timber — a wood panel product made from gluing together layers of timber that come from carefully managed farms — as a promising alternative to increasingly scarce old-growth trees and carbon-emitting concrete.

“European cities have created these great, historic landmarks. We have the Space Needle, but we also have the Olympic Mountains, the lakes, Mount Rainier. Those are our Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe.”

Between 2016 and 2019, Jones served on the 18-person International Code Council’s Tall Wood Building Committee, which helped change national building codes to allow wood high-rise buildings up to 18 stories. She is currently working on Heartwood, an eight-floor multifamily housing project in the Capitol Hill neighborhood that will open this spring. It will be the first Type-IV-C IBC Building Code building (which has to do with height and materials) permitted in Seattle and the first in the U.S. under construction.

“One of the things I’m trying to do with our practice, and through the use of mass timber, is bring back the notion of collective living and make it a more open, equitable, and diverse experience,” she says. “Wood shouldn’t become so precious that only a handful of people can afford it.”

Housing affordability has become one of the biggest hot-button issues in Seattle during the past two decades. In the 1990s, the city began experiencing an economic and population explosion. By the mid-2010s — as major tech companies offered six-digit salaries to many of their employees — rent prices skyrocketed, and developers flocked to Seattle to build uninspired, cookie-cutter “luxury” apartment and condo buildings. South Lake Union became the hottest real estate market in the country.

Rising rental and real estate prices have pushed thousands of people from their homes. The city last year invested $250 million in affordable housing, but prices still remain out of reach for the majority of city residents.

With new people come new ideas and fresh points of view. Northwest Modernism had a stylistic stronghold for years with architects such as Olson, Suyama, Tom Kundig, L. Jane Hastings, Jim Graham, and Eric Cobb evolving it on the residential scale. But many of today’s emerging small- to-mid-sized firms such as Best Practice, GO’C, SHED, and Mutuus are less concerned with embodying a “signature” look or following in anyone’s footsteps.

Instead, they focus on holistic approaches that consider the physical, social, and cultural contexts surrounding each project, as well as the impact they will have for years to come.

Some firms are also stepping away from the understated, all-wood, beige-and-tan aesthetic of the 1990s and early 2000s. Think more color, industrial materials, and new forms that show global influences. Where other cities such as New York and Los Angeles are hemmed in by density and topography, Seattle has had more flexibility to expand northward and southward. That has resulted in a continuation of the single-family home ideal that continues to this day. But as more people come to the city, additional forms of housing will become imperative, especially in order to maintain a thriving, active downtown core.

“Our firm is in this unique place where we have an opportunity to help define the future of Seattle architecture,” Gregga says. “We’re not building these old-school Seattle Modern houses but we’re also not participating in the fast-paced developer culture. We care about the existing single-family fabric, but we also don’t think that it is too precious to touch.”

The pandemic also created opportunities to revitalize the downtown core. With an increasing number of companies transitioning to remote work, formerly bustling office buildings stand vacant. Many of those spaces have the potential to become retrofitted into housing, though city building and zoning codes currently make that difficult. The ambitious $1 billion-plus makeover of Seattle’s waterfront has sparked a rethinking of the urban landscape.

“We have the best setting in the world,” Olson says. “We can either take advantage of it or we can waste it. I think now is the time to look at what we’re doing and make the choice to take advantage of it so that our residential landscape only improves.”

Both Olson and Suyama worked together at the end of the 1960s in the architecture office of the late Ralph Anderson, who was instrumental in efforts to preserve both Pike Place Market and the Pioneer Square neighborhood. They cite those years as a formative experience that influenced their penchant for Modernism and historic preservation.

“There’s hope and incredible potential for Seattle,” Olson adds. “If we take care of the city and manage it properly, it can it become something truly great.”