Features

Nationally Touring Play ‘Cambodian Rock Band’ Uses Music As A History Lesson

The play, by Lauren Yee, offers a glimpse of the country’s pre-Khmer Rouge music scene, with songs by Dengue Fever alongside classic Cambodian oldies

By Samantha Pak October 13, 2023

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2023 issue of Seattle magazine.

Cambodia of the 1960s and ‘70s boasted a thriving music scene. With artists combining traditional Cambodian music forms with global rock and pop influences from the United States, Europe and Latin America, they created a unique sound—which was all sadly cut short when the Khmer Rouge took over the country in 1975.

Many musicians from this era either disappeared or were killed by Pol Pot’s genocidal regime. And while these artists may have been lost, their legacy still lives on today. The most recent example of this is Lauren Yee’s play Cambodian Rock Band (CRB).

The play tells the story of Chum, a Khmer Rouge survivor returning to Cambodia in 2008 for the first time in 30 years, as his daughter Neary prepares to prosecute one of the country’s most notorious war criminals. As the play jumps back and forth in time, Chum must confront his past as he finally shares it with Neary. The “play with music,” as Yee describes it, is backed by a live band (cast members doubling up as the musicians) playing contemporary hits by the band Dengue Fever, as well as classic Cambodian oldies.

The show has been touring since January, with stops all over the country, including in Houston, Berkeley, California, and Washington, D.C. They’re finishing this round of touring in Seattle, with opening night on Oct. 5 and shows through Nov. 5 at ACT Theatre.

CRB’s origins can be traced back to 2011 when Yee was in grad school and first saw Dengue Fever perform. After hearing their music, which combines the aforementioned Cambodian rock with psychedelic rock, the Chinese American playwright went down a rabbit hole as she researched the band’s influences. As a result, Yee also learned more about Cambodian history—something she hadn’t known much about since most AA+PI history still just barely skims over the conflicts of Southeast Asia.

Francis Jue in “Cambodian Rock Band.”

Photo by Margot Schulman

“You know nothing about Cambodia. At best, you learn a little bit about the Vietnam War,” Yee says about her experiences as a student.

She took her newly found knowledge and turned it into CRB, after she was commissioned by South Coast Repertory—which in Costa Mesa, California, is a mere 30 minutes from Long Beach’s Cambodia Town—in 2015 to write a play that focused on the local communities. The show premiered at South Coast in 2018.

A conversation starter

When Yee was workshopping CRB, one of the actors who was part of that process was Joe Ngo, who plays Chum, the father and story’s lead.

Ngo immediately connected with CRB, telling Yee that it was his story as a Cambodian American. As is the case with most people in our community, he has a direct connection with the Khmer Rouge—like me, his parents are survivors. Ngo’s uncle also used to be in a live band, which is how that became part of Chum’s history.

In every city, CRB holds Khmer community days as outreach to the local community and to get people to the theater…These days sometimes include talkbacks with the cast after the show, so they have those difficult conversations about this dark moment in our shared history, but in a healthy way.

When Ngo was first cast, his parents weren’t sure he should be involved with the show because of its dark subject matter—the show could traumatize (or retraumatize) people. But Ngo says there’s been a deep healing that has happened at their shows. In every city, CRB holds Khmer community days as outreach to the local community and to get people to the theater—which isn’t always accessible, for a number of reasons. These days sometimes include talkbacks with the cast after the show, so they have those difficult conversations about this dark moment in our shared history, but in a healthy way. The community day in Seattle will be Oct. 7. Ngo, who says these community days are always his favorite part of the show, also points out that this is the crux of CRB, as his character is finally forced to talk about his past with his daughter.

And even if a community day doesn’t include a conversation with the cast, Ngo is confident their show has prompted conversations among families. Just as it did with his family when they came to see the show—including his parents, as well as his musician uncle and cousins.

“I know that on that ride home, he’s going to talk about it,” Ngo says about his uncle, who saw the show with his kids in Washington, D.C.

In “Cambodian Rock Band,” (from left) Brooke Ishibashi and Joe Ngo play daughter Neary and father Chum.

Photo by Margot Schulman

Ngo’s parents weren’t the only ones who were worried about him taking on this role of a Khmer dad. Ngo feared people would think he was playing a parody or mocking his own dad and he was “really concerned with how to get it right.” He had to figure out how to honor the Khmer patriarch.

When he finally figured it out and settled into his role, the community took notice. Ngo says he’s had Khmer kids tell him they see their own dads in his character. Even better, Ngo’s aunts and uncles who have seen the show have told him that they see their brother. Part of this is Ngo throwing in what he calls “Khmerisms” while playing Chum, such as hitting his fellow cast members when he talks to them (he’s warned them ahead of time that he would be doing this).

“I’m completely unapologetic about it,” he says with a laugh.

While hitting someone while speaking to them may be singular to Ngo, who is the only Khmer cast member in CRB, he says it’s also universal to Khmer folks. And he’s right. I immediately know what he’s talking about—that’s just how some of us speak.

Putting in the work to get it right

As someone who is not part of the Khmer community, Yee took her responsibility as the writer very seriously. Her research process happened over the course of a few years. There was a lot of reading up on this period of Cambodian history, watching documentaries including Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock & Roll and talking with members of the Khmer community about their experiences—the dark as well as the joyful. Her dialogue with community members also included questions about what they needed and wanted to see on stage.

And that effort to get things right is ongoing. The show has also hired Sokunthary Svay as a Khmer vocal coach. Svay, a writer and poet who also has a background in opera, works with the actors on their Khmer pronunciation and diction, as well as to contextualize certain aspects of the musical and vocal performances. She’s also worked with the performers on vocal techniques so they sound like Khmer singers, versus someone just singing in Khmer.

“Cambodian Rock Band” will run in Seattle through Nov. 5.

Image by DC Scarpelli

Svay demonstrated this to me, singing a verse two different ways and as someone who’s grown up hearing Khmer music at parties, I immediately recognized the difference. Khmer singers tend to have a nasal quality to their voices that western singers typically don’t.

Svay—who was born in a Thai refugee camp and grew up in the Bronx, New York, when her family came to the United States—says as a member of the Cambodian diaspora, she understands people’s skepticism about CRB, with it being written by a non-Cambodian. But Yee puts in the work and bringing people together in the form of the Khmer community days shows she’s here for the community, Svay says.

“(People are) totally right to feel this way,” Svay says. “But reserve judgment ‘til you see it…I feel proud and grateful (to be involved) because it’s clear to me that they are about doing it to the best of their abilities and getting it right.”

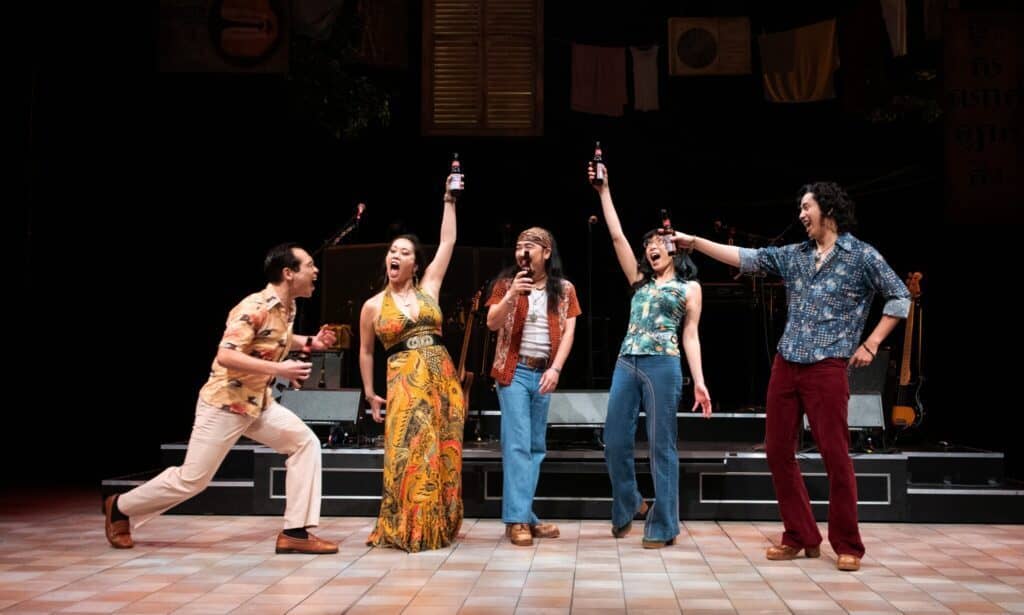

From left, Joe Ngo, Brooke Ishibashi, Abraham Kim, Jane Lui and Tim Liu in “Cambodian Rock Band.”

Photo by Margot Schulman